|

|

Le

Char à Boeufs – Souvenir de Bretagne

The Ox Cart –

Recollection of Brittany

Guérin 70, Mongan,

Kornfeld & Joachim 51

woodcut, 1898-89, on tissue-thin white Japon paper, finely laid down on another Japon

paper with good margins on three sides (Paul Gauguin most often trimmed

his impressions down closely, sometimes significantly into the

composition*);

signed by the artist in black ink with his initials "P.G." lower right, and numbered "- 2 -".

P.178x292mm., S. 203x305mm.

|

Provenance: originally Gustave

Fayet, Beziers (who was one of Paul Gauguin's early friends and

collectors); Galerie André Candillier, Paris; private collection,

Switzerland; Christie's, London, 3-4 December 1996 [lot 375];

Bonham's, San Francisco, April 30, 2013 [lot 37]*; acquired at the

previous sale by the late owner.

Gauguin returned from Tahiti to France for the last time in July 1893, spending two years, mostly between

Paris and Brittany, with a final stay in Pont Aven during 1894.

This print is

dated to 1898-89 and is part of the set of late block prints that

Gauguin made in Tahiti after his return in 1895; there is a picture

with the same subject, titled Nuit de Noël

(La Bénédiction des Boeufs, right), now in the Indianapolis Museum of Art, that is usually dated earlier and is rather hard to date. Gauguin

could have begun work on it in 1894 during his stay in Pont Aven (as per the Wildenstein catalogue dating, see W519 therein), but most probably it was completed

in Tahiti, where it was found after his death in the studio, and thus

is also dated to 1898-99 or even 1902-1903.

It has the same snow-covered houses in the background, but the figures

are different, and the oxen are seen hieratically standing before a

large granite niche with a  Nativity scene, which is lacking in the

print. Did Gauguin intend to add the Nativity in the dark blank

space to the right in the Char à Boeufs, so as to specify the subject of the print?

Nativity scene, which is lacking in the

print. Did Gauguin intend to add the Nativity in the dark blank

space to the right in the Char à Boeufs, so as to specify the subject of the print?

We

know that Gauguin intended to use this print as the centerpiece of a

triptych of woodcuts, with Le Calvaire Breton (left) set to the left and Misères Humaines (below, right) to the right. (See the cogent discussion by Richard Brettell of this woodcut series in the Gauguin exhibition catalogue, RMN, Paris 1989, pp. 417-421, as well as their theoretical assembly reproduced in the Art Institute of Chicago study of Gauguin's woodcuts.**.)

In this context, the Calvaire Breton is scenographically compatible with the Char à Boeufs,

as it has the same snow-capped houses and snow-bound hills in the background, the same team of oxen (as in the picture), in right

profile, and the palissade to the far right, abutting that of the Char à Boeufs. If each sheet were trimmed to whatever width, they would fit well.

The subject of

Gauguin's picture (and by extension the woodcut), however, is not just a

wintry village scene. It relates more especially to well-known Breton folklore: it is said that the animals, on Christmas Eve, steadfastly keep watch (it is said that only toads and humans sleep!),

and they speak together in human tongue with the uncanny ability to foresee the future.***

especially to well-known Breton folklore: it is said that the animals, on Christmas Eve, steadfastly keep watch (it is said that only toads and humans sleep!),

and they speak together in human tongue with the uncanny ability to foresee the future.***

Given his

interest in such lore, both in Brittany and Tahiti, Gauguin was most

certainly aware of this belief and it should well have influenced his

work, as well as the scenography here present.

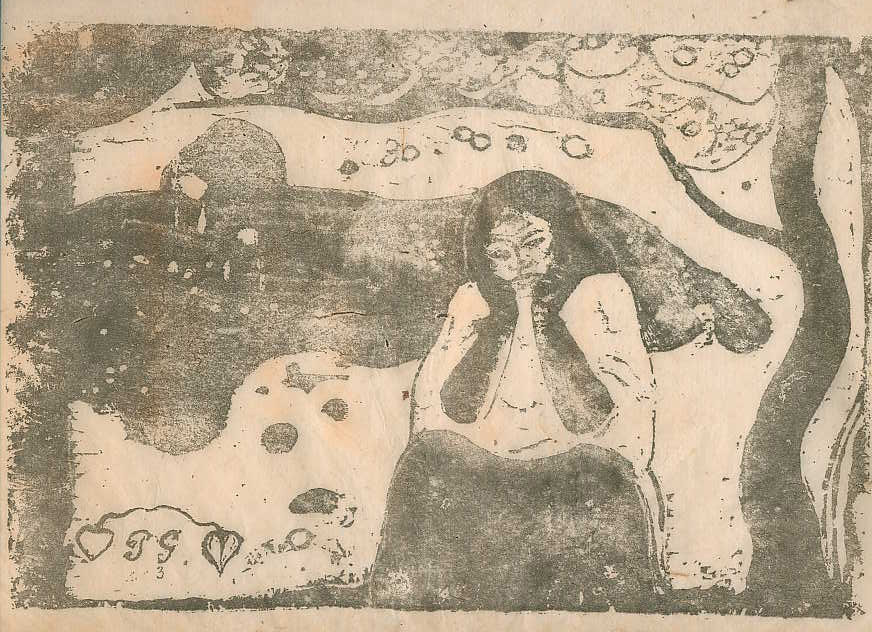

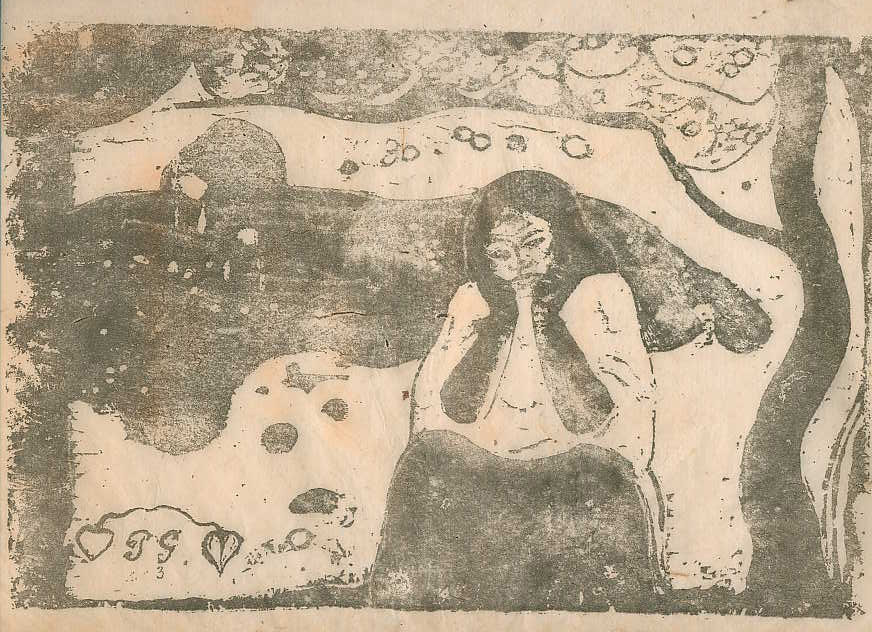

The woodcut of Misères Humaines (right) shows an equivalent dark blank slab along the far left that would fit perfectly against that on the right of the Char à Boeufs.

Would Gauguin have intended to use the abutting space in the two prints

to figure a scene of the Nativity, as in the picture?

The scenography

seems less appropriate however, as it concerns an autumnal

grape-harvest scene (originally set in Arles, but here populated with

bent-over Breton women). The melancholic woman in the foreground,

head despondently clasped in hands, however seems more Tahitian!

What is she lamenting in fact? Would she in fact be a Gauguinian

alter-ego down south, caught up in deep recollection (as the subtitle

of the Char à Boeufs

suggests) of his bygone days in Brittany? A tempting

conclusion... that would indeed make sense of the virtual triptych as

Gauguin intended.

* Mongan,

Kornfeld & Joachim give the dimensions as 160 to 195 and 260 to 295mm, "due to the uneven inking of edges of block." (The original woodblock is apparently unknown.) There is an impression of this print in the Five Colleges

collection, signed and numbred "12", that is rather more palely inked

than ours, but shows the full extent of the right margin for the

original matrix:

https://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?t=objects&type=ext&id_number=SC+1972.50.53

** See https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/141096/section/140419

*** See François-Marie Luzel, Légendes Chrétiennes de la Basse Bretagne, Paris 1881, pp. 329 et seq. In one of the legends, on Christmas Eve, a large red ox spoke thus:

- Our Lord is born, my

children, the merciful and almighty God, and he was not born in a

palace or in the house of a rich man of the earth;

he came into the world, like the

last of the unfortunate, in a manger, between an ox and a donkey! Glory

to the Lord!

- See also:

https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/L%C3%A9gendes_chr%C3%A9tiennes_de_la_Basse-Bretagne/Veill%C3%A9e_bretonne

and

-

http://www.tresor-breton.bzh/2019/12/29/les-animaux-se-parlent-en-breton-la-nuit-de-noel/

Nativity scene, which is lacking in the

print. Did Gauguin intend to add the Nativity in the dark blank

space to the right in the

Nativity scene, which is lacking in the

print. Did Gauguin intend to add the Nativity in the dark blank

space to the right in the  especially to well-known Breton folklore: it is said that the animals, on Christmas Eve, steadfastly keep watch (it is said that only toads and humans sleep!),

and they speak together in human tongue with the uncanny ability to foresee the future.***

especially to well-known Breton folklore: it is said that the animals, on Christmas Eve, steadfastly keep watch (it is said that only toads and humans sleep!),

and they speak together in human tongue with the uncanny ability to foresee the future.***