|

|

Le

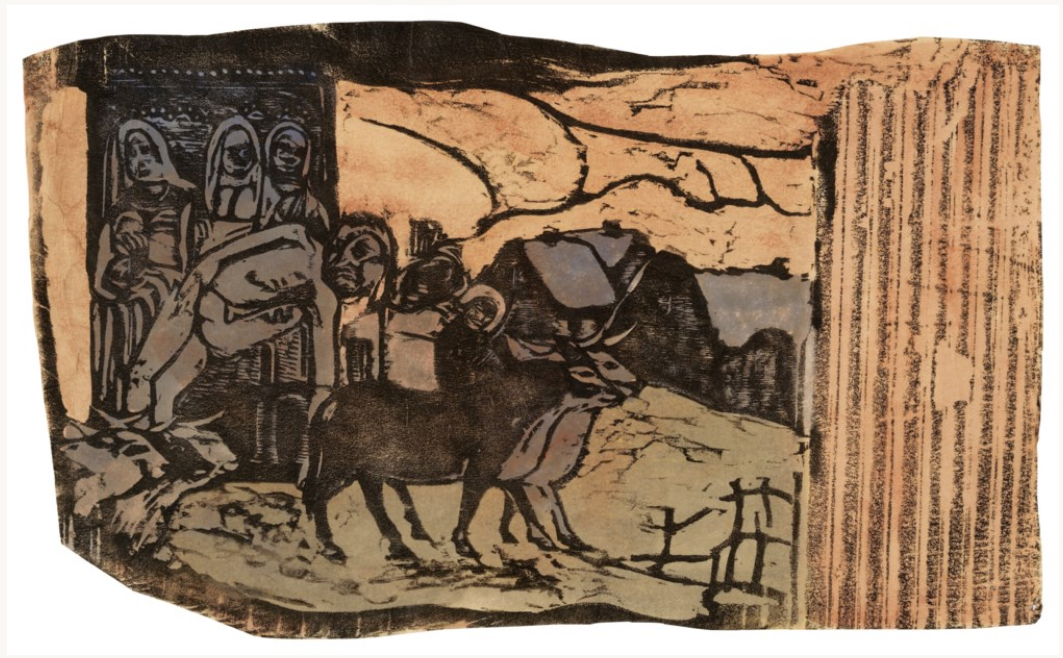

Calvaire Breton

The Wayside Shrine in Brittany

Guérin 68; Mongan,

Kornfeld & Joachim 50

woodcut, 1898-89, on

tissue-thin Japon

paper, finely laid down on medium-heavy tan-beige wove paper, with a narrow

margin on the left and slightly trimmed into the subject elsewhere

(Paul Gauguin most often cut

his impressions down closely, sometimes significantly into the

composition)

signed by the artist in black ink with his initial "P" lower right, and numbered "28",

exceptionally with uniformly monotyped orange-ochre toning to the sheet by the

artist before printing of the image; the print itself is very fine

condition, with no defects visible aside from a fleck of black ink

lower left

S.

150x227mm.* (The original woodblock, now held in the Bibliothèque

Nationale de France, measures 165 × 265mm overall)

|

Provenance: formerly in the collection of the art historian,

Lawrence Saphire (not listed among the 17 impressions that Mongan,

Kornfeld & Joachim identify)

Gauguin

returned to France

from Tahiti in July 1893, spending two years, mostly

between

Paris and Brittany, with a final stay in Pont Aven during

1894. Back in Tahiti the following year, he undertook his last

printmaking project in 1898-99, mixing Tahitian and Breton themes,

often in the same series.

Le Calvaire Breton

is usually dated to

1898-9, as one of his late woodblock series, well after his return to

Tahiti, though it incorporates the Deposition of Christ from the 15th

century Calvary of Nizon, near Pont Aven**, which Gauguin painted in

the picture of the same title, Le

Calvaire Breton or Christ Vert

in 1889 (Wildenstein 328 , now in the

Musées Royaux

des Beaux Arts de Belgique, below,

left).

To the print,

in place of the rugged Breton dunescape in the picture, Gauguin added a hilly winter village background with a cluster of

houses and teams of oxen moving across the

front of the scene, to the right, toward

what would appear to be an enclosure.

We

know that Gauguin

intended to use this print as the leftmost panel of a

triptych of woodcuts, with the Char à Boeufs set in the middle

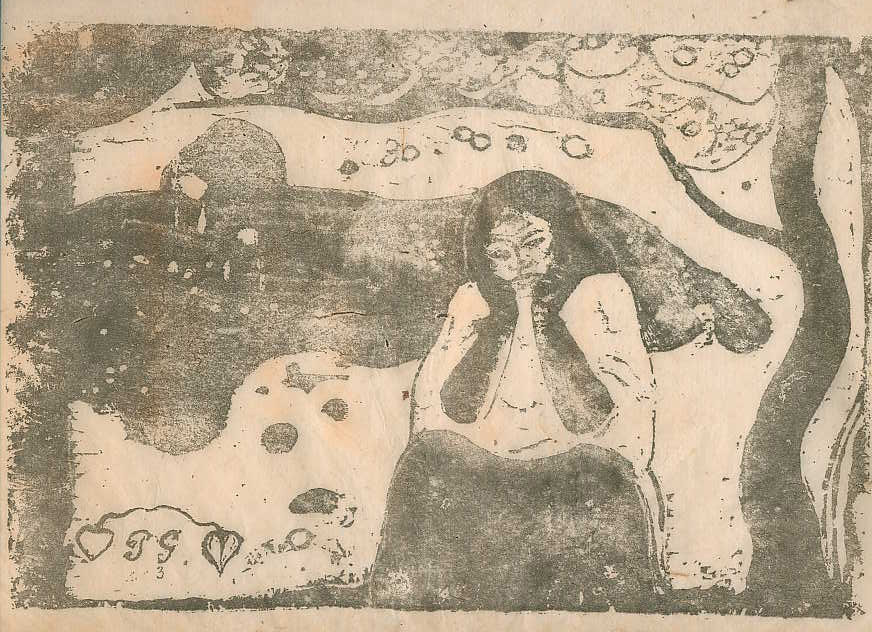

and Misères Humaines (below, right) to the right. (See

the cogent discussion by Richard Brettell

of this series in

the Gauguin

exhibition

catalogue, RMN, Paris 1989, pp. 417-421, as well as their theoretical

assembly reproduced in the Art Institute of Chicago study of Gauguin's

woodcuts.***)

In this

context, the Calvaire is

scenographically compatible with the Char

à Boeufs,

as it has the same snow-capped houses with snow-bound hills in the

background, and the same hieratically

aligned oxen. With the palissade to the far right, abutting that of

the Char à Boeufs, it may be

seen that if each sheet

were trimmed to whatever width, they would fit well. The Art

Institute of Chicago's Technical

Study

also includes a demonstration that the two wood blocks were probably

hewn from the same plank of indigenous wood, which reinforces Gauguin's

intent.

The subject of

Gauguin's scenography however, is not just

a

wintry village scene. It relates more especially to well-known

Breton folklore: it is said that the

animals, on Christmas Eve, steadfastly keep watch (it

is said that only toads and humans

sleep!),

and they speak together in human tongue, with the uncanny ability to foresee

the future.**

Given his

mystical

interest in such traditions, both in Brittany and Tahiti, Gauguin was

most certainly aware of this belief, which

would have influenced his

work, as well as the Breton scenography here present.

It should be

added too that our impression is a good example of Gauguin's

exploration of color in his late woodcut printmaking. Gauguin began experimenting

with color in the Noa Noa series of woodcuts, and his

coloring is rather varied: most often with the application of earth

colors,

sometimes in zones or a thinned, uniform toning, elsewhere

as a watercolor wash, either applied in zones before printing the

keyplate, other times applied directly over the impression.

These

various techniques have been studied in

depth by a curatorial team

from the the Art

Institute of Chicago.****

Our

impression is marked by a flat color

field of ochre, which the AIC call

"transfer coloring": in this technique the artist spreads a film of ink

over a flat matrix which is then impressed onto the blank sheet.

We know of one other impression of Gaugin's Calvaire Breton with additional hand coloring from the Kelton Collection (right), which is chromatically

comparable to ours in the background color field, and which Gauguin

ostensibly intended to connote the culminating events of the Passion:

the Deposition from the Cross and the Lamentation of Christ by the

three Marys. Several of the Evangelists relate that, during the

Crucifixion, darkness spread across the land and the sun stopped shining, and this may well have inspired Gauguin's represention of the scene here.

Gauguin's

concern with religious themes in any case ran through a good part of

his life, and was summed up in the unpublished work, L'Esprit Moderne et le Catholicisme

(now in the Saint Louis Art Museum, see

https://www.slam.org/collection/objects/18302/?ocaid=modern-thought-and-catholicism-gauguin#mode/2up)

a synthetist approach to the religions of the world that he completed

in the Marquesas in 1902, and which here is evident in the cortege of

oxen, moving from Calvary to the Nativity.

* Mongan,

Kornfeld & Joachim

give the dimensions of the early impressions as 161 x250 mm,

again most ofen cut down, in variable formats.

Cf. the Art institute of Chicago

impression, from the renowned Marcel Guérin collection, at

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/60634/wayside-shrine-in-brittany-from-the-suite-of-late-wood-block-prints,

where the dimensions of the

trimmed sheet are given as 152 × 227 mm; in comparison, our

impression is cropped slightly along the top border.

Cf. also the impression sold at Sotheby's

(https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2022/prints-multiples/le-calvaire-breton-g-68-k-50),

which is cropped more markedly into the left edge of the composition and along the bottom

**

https://monumentum.fr/monument-historique/pa00090287/pont-aven-calvaire

***

See https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/141096/section/140419,

and especially the analysis by Harriet Stratis:

"Gauguin took

the thick, irregular pieces of wood he found in Tahiti, including more

rectilinear planks, and crudely cut them down laterally to reduce their

thickness. Taking into consideration that the indigenous wood was not

commercially

manufactured into regularly sized blocks, the unusual,

irregular contours and grain in the wood used by Gauguin provide

topographical reference points that allow them to be matched and

paired. Five such pairs were identified during the course of this

study. These include Wayside Shrine in

Brittany and The Ox

Cart"

(See in particular: https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/141096/section/140412/p-140412-17)

**** See

François-Marie Luzel, Légendes

Chrétiennes de la Basse Bretagne, Paris 1881, pp. 329 et seq. In one of the legends, on

Christmas Eve, a large red ox spoke thus:

- Our Lord is born, my

children, the merciful and almighty God, and he was not born in a

palace or in the house of a rich man of the earth;

he came into the world, like the

last of the unfortunate, in a manger, between an ox and a donkey! Glory

to the Lord!

- See also:

https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/L%C3%A9gendes_chr%C3%A9tiennes_de_la_Basse-Bretagne/Veill%C3%A9e_bretonne

and

-

http://www.tresor-breton.bzh/2019/12/29/les-animaux-se-parlent-en-breton-la-nuit-de-noel/

***** See Daher, Sutherland, Stratis, & Casadio, Paul Gauguin's Noa Noa prints:

Multi-analytical characterization of the printmaking techniques and

materials, in Microchemical

Journal, 2018, 138, pp.348-359.

There is also a

video demonstration of these printing

techniques that the Art Intitute of Chicago has produced, now visible

online here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eoVT2UZ_drs