|

Exhibition

|

|

Exhibition

|

This exhibition concerns a rare and astonishing album of engravings first published in 1806, finely reproducing Charles Le Brun's physiognomies - comparative drawings of human and animal faces - that had been made over 135 years earlier.

Charles Le Brun (1619-1690) , First Painter to the King Louis XIV, was the founder of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, and the foremost proponent of French classicism. On 28 March 1671, addressing the Royal Academy, he formally presented his treatise:

"all of the various demonstrations that he has drawn, whether heads of animals or heads of men, making note of the signs that mark their natural inclination." (Procès-verbaux de l'Academie I : 358-359)

While the set of drawings** is still conserved in the Louvre, the original text has been lost: we have but a rough synthesis by Nivelon, posthumous digests by Henri Testelin and E. Picart, and the dissertation by Morel d'Arleux accompanying the 1806 edition of the engravings.

Louis-Jean-Marie Morel d'Arleux (1755-1827) was curator of drawings and prints at the Musée Napoléon (today the Musée du Louvre). His interest in Le Brun's "demonstrations" and his devotion to their revival are noteworthy, and relate to the current of neo-classicism then in vogue, a conceptual triangulation linking the Roman and the Napoleonic imperium through the reign of the Sun King.***

Physiognomy,

literally the "knowlege of nature," relates to the assessment

of human character through study of physical features. This concept

of an inherent concordance of body and soul harks back to Antiquity,

and regained currency in 17th-century thought.

Le Brun of course drew on various contemporary sources, both graphic

and philosophical, two of which come immediately to mind:

G. B. Della Porta's De Humana Physiognomia had been translated into French in 1655-56, and certain of Le Brun's drawings relate closely to his Italian predecessor,

and more importantly, René Descartes published his Passions de l'Ame in 1649, identifying the seat of the soul in the pineal gland, located at the centre of the brain.

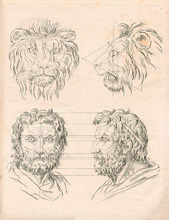

Le Brun took this as a starting point for his treatise. Elaborating a geometry that links the soul to the senses, in witness of faculties and character, he studied the lines relating the different features of the head. The angle thus formed by the eyes and the browline is here indicative of the individual's aspirations: directed upward they would be lofty and spiritual; downward to nose and mouth, the animal elements of base sensory experience, they would be vile (see Plate 1).

Thus the position and the conformation of the eyes greatly help to read the dominant passions (Cf. the demonstration in Pl. 12, where Le Brun bestows human eyes on the lion and the horse).

As related by Henri Testelin (in his 3ème Discours Académique),

"The affections of the soul follow the temperament of the body and the external marks are certain signs of the affections of the soul, that we know in the form of each animal, its mores and its complexion...

The difference between the human face and that of the brutes is that man has eyes located on the same line that traverses straight to the nerve of the ears, which leads to the sense of hearing; the brutish animals to the contrary have the eye drawing downward to the nose, following their natural affections."

Testelin follows up on the geometry in animals, stating:

"It was demonstrated by a triangle that the sense impressions [i.e. feelings] of animals are borne from the nose to the ear, and from there to the heart, of which the bottom line comes to close up the angle with that of the nose; and that when this line traverses the whole eye, and that on the bottom passes through the mouth, this marks the animal as fierce, cruel, carnivorous.

There is also a small triangle of which the point is at the outside corner of the eye; whence the line following the contour of the upper eyelid forms an angle with that coming from the nose. When the point of this angle meets toward the brow, it is a mark of mind ("esprit"), as is seen in elephants, camels, and monkeys; and if this angle falls on the nose, this marks stupidity and imbecility, as in asses and sheep..."

Le Brun's system is in fact two-tiered, having to do with general characteristics, yet taking account of individual differences.

As Morel d'Arleux puts it:

"He had to find signs with the help of which one could measure the extent of faculties, distinguish the natural instinct of each species, and the particular penchant of each individual."

Did Le Brun really believe in a semiotics of soul? That there are universal features in all life forms of which mathematical study could reveal their nature? From his demonstration at least, it would seem he meant to assure us that certain people have more in common with the beasts than with their fellow man. Let's take a closer look...

* "The first 11 plates were engraved by Mr. [Louis-Pierre] Baltard and the others by Mr. André Le Grand" according to the title page of the 1806 edition; for the catalogue of a recent exhibition of the engravings, see Madeleine Pinault Sørensen, De la physionomie humaine et animale : dessins de Charles Le Brun gravés pour la Chalcographie du Musée Napoléon en 1806, RMN, Paris, 2000.

** For the original drawings, see Lydia Beauvais, Inventaire Général du Fond Français du Louvre, Dessins de Lebrun, RMN, Paris 2000.

*** The Chalcographie itself grew out of Colbert's creation of the Gobelins factory for Louis XIV (which included an engraving workshop under Sebastien Leclerc), and it is well known that Napoleon was instrumental in its revival, commissioning works to commemorate his reign, as well as works he deemed of great interest, such as the album presented here.

engravings, 1806, on heavy laid paper, with alternating watermarks of a dovecote and "G FENEROL/AMBERT"; the complete set of 58 plates on 37 sheets as published in the first edition, fine impressions with full margins (except Plate 12, trimmed 9mm laterally), with traces of the old binding (stitching and perforations along the left edge), some slight foxing as well as handling creases overall, the sheet edges on certain plates somewhat soiled, nicked, and scuffed, a marginal tear on Pl. 24b (well away from the subject), a few other short tears, the last few plates marginally waterstained, occasionally extending into the image (see notably Pl. 32 and 33), Plate 1 slightly soiled and scuffed, and the last sheet soiled overall on the reverse, otherwise in relatively good condition

Bibliography: Brunet III, 910

N.B. For practical reasons, and given the size of the prints, we have decided to show them here in series, on a relatively small 1 : 6 scale, and divided into two parts:

Part I (here following) contains Plates 1-11, which are essentially line engravings, serving more demonstrative ends, but grouped into 2 subsets: the human exposition (Pl. 1-5) and the animal extrapolation (Pl. 6-11);

Part II contains Plates 12-37, much more finely engraved, serving more illustrative ends, which develop the argument; on the basis of Pl. 12 , which takes up the eye motif, Le Brun develops a parallel set of animals, the plates again grouped into two subsets: the equivalent heads of man/animal (Pl. 13-33), and the four last plates of eyes (Pl. 34-37), the most surrealistic of all,

and with each of the larger images (1 : 3 scale) visible on a separate page.

Here Le Brun sets forth the basic premises of his argument.

He develops the canons of the human face, with the inclination of the eyes as the main index of an individual's elevation or abasement. A physical predisposition, the axis of vision (eye-soul), orients the "passions".

This argument is further illustrated by classical examples: gods and heroes, as well as the Roman emperors Antoninus and Nero.

|

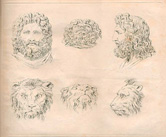

Plate 3. Heads of Jupiter and LionsThough the relationship to the lion here is unclear, it ostensibly reflects an interplay of serenity, courage, and ferocity. P. 271x327mm., S. 590x430mm. |

Here Le Brun develops the triangular geometry relating to what he apparently considered to be significant examples of animals, along with their human equivalents. Drawing on Testelin, Morel d'Arleux comments thus:

"He [Le Brun] supposed an equilateral triangle, of which the base AB, passing through the inside of the eye at E, finding itself cut off at point A, at the tip of the nose and at point B, either the tympanum of the ear or the base of the horns...

If the animal was carnivorous, he drew a parallel to the side BC of the triangle that ran through the inner corner of the eye at E, cutting more or less across the mouth at G, according to the voracity, but that would be found well inside if it were herbivorous . This same parallel extended to the brow was to strike the sign of strength, indicated by a greater elevation of this part and denoted at the same time the degree of an animal's courage.

The line HI, starting from the outer corner of the eye next to the upper lid and extending to the brow, reveals the degree of an animal's sagacity by its elevation, of mansuetude by its tending to the horizontal, of meanness or abasement by an inclination on the nose.

The outer parallel KL, drawn to the base AB of the triangle ACB and grazing the highest elevation of the brow, comes to bear on the preceding observation, leaving more or less room between it and the muzzle according to whether or not the animal is endowed with intelligence."

|

Plate 7. Relationship of the Human Figure with that of the OxThe ox is characterized by both strength and obstinacy.

P. 434x325mm., S. 590x430mm. |

|

Plate 9. Relationship of the Human Figure with that of the HogThe hog is equated with lubricity and gluttony.

P. 436x326mm., S. 590x430mm. |

|

Plate 10. Relationship of the Human Figure with that of the LionHere the lion's fierce and carnivorous aspect is underscored.

P. 434x321mm., S. 590x430mm. |

|

Plate 11. Relationship of the Human Figure with that of the MonkeyThe monkey was considered by Le Brun to show signs of intelligence ("esprit").

P. 353x297mm., S. 590x430mm. |