|

Exhibition

|

|

Exhibition

|

Here we intend to show sets of fine prints, either small thematic collections, whole series, or albums of special interest, with some general remarks as to their creation and their importance.

This space will be renewed regularly, with the previous shows accessible thereafter in the Archives.

The present exhibition concerns

an unbound proof copy of Parallèlement, with the

rare lithographic colour variants in bistre. One of the masterpieces

of 20th-century illustrated books, it is generally considered

to be the first modern livre de

peintre.

Ambroise

Vollard (1868-1939), French art

dealer, publisher and collector, was probably the most significant

figure in the emergence of modern art and Parallèlement,

his first illustrated book, was a sumptuous undertaking that now

stands as a milestone at the forefront of this development.

Ambroise

Vollard (1868-1939), French art

dealer, publisher and collector, was probably the most significant

figure in the emergence of modern art and Parallèlement,

his first illustrated book, was a sumptuous undertaking that now

stands as a milestone at the forefront of this development.

Vollard was painstaking in the realization of his project: he exclusively commissioned a fine-grained medium-heavy Dutch wove paper ("vélin de Hollande") from the renowned Van Gelder manufactory in Amsterdam, with the watermark PARALLELEMENT, and, having chosen a Renaissance font originally designed by Garamond in 1540 for François I and newly cast for the occasion, he had the text set and printed by hand at the Imprimerie Nationale. Bonnard's original lithographs were hand-printed by Auguste Clot, at the foremost lithographic workshop in France, in a subtle rose-sanguine ink that Bonnard had demanded so as to better render Verlaine's "poetic atmosphere."

"It is not astonishing that Ambroise Vollard had Bonnard in mind to illustrate Verlaine's Parallèlement. He knew the artist's drawings for Marie, and he had seen the picture L'Indolente, of which moreover a drawing would appear in the work, at the group exhibition organized at Durand-Durel in May 1899. To accompany Verlaine's poems, Bonnard invented an irregular composition; the lithographs play with the stanzas, interlace with them, mingle with them or slip off into the margins, voluptuous and tender images whose power of suggestion miraculously blends with the poet's art." *

Pierre

Bonnard (1867-1947) was already

a well-known artist at the time, one of the leaders of the emergent

Nabis group, who were revolutionizing French art at the turn of

the century.

Pierre

Bonnard (1867-1947) was already

a well-known artist at the time, one of the leaders of the emergent

Nabis group, who were revolutionizing French art at the turn of

the century.

With a strong interest in the graphic arts, especially colour lithography, by 1900 he had realized over 70 lithographs (posters, illustrations, and fine prints), including albums for Vollard.

Bonnard worked fervently on the project, mainly drawing inspiration from his own resources to capture the sensual intimacy of the poetry: many of his paintings from the late 1890s were quite attuned to Verlaine's vision, in particular the nude portraits of Marthe, his companion, and would serve as the groundwork for a number of the lithographs (L'Indolente, Dauberville 219, 01802, 01803; Nu aux Bas Noirs, D. 01829; L'Homme et la Femme, D. 224). Using a portable Kodak camera, he further realized a series of nude photographs** of Marthe in his apartment, rue de Douai, capturing in a casual snapshot style, with informal framing, what would become the sketchy freedom of the Parallèlement illustrations.

Paul Verlaine (1844-1896), "poète maudit,"

had become something of a legend by the turn of the century, and

it is worthwhile to review briefly the origins of Parallèlement

and why it was to gain Vollard's attention.

Paul Verlaine (1844-1896), "poète maudit,"

had become something of a legend by the turn of the century, and

it is worthwhile to review briefly the origins of Parallèlement

and why it was to gain Vollard's attention.

Between 1885-87, while preparing the work, and following the divorce with his wife, Mathilde (after 15 years of tumultuous marriage), the poet was practically reduced to beggary and chronically ill, often hospitalized, in the most troubled period of the artist's life.

Parallèlement is however a varied collection of poems written at different periods, and brought together to meet one of the poet's preoccupations. In his preface*** to the first edition (1889), Verlaine explains the title as part of a vaster poetic project, in "parallel" to Sagesse, Amour, and Bonheur, which expressed his earlier mystical aspirations to a Christian spirituality of religious faith and moral values. Parallèlement is however grounded in the other "infernal" side of human nature, notably taken up with the flesh rather than the spirit, the exaltation of erotic desires and polysexuality (e.g., Les Amies, in praise of lesbian love, or Filles, in which Verlaine takes up the theme of the brothel and his multiple affairs).

Vollard's ambition in creating the first modern livre de peintre was thus to integrate the poet's powerfully evocative text and the painter's sensual, spontaneous, and allusive lithographs. With the stanzas printed sparingly in a refined typeface, laid out in an ample format, the book afforded the lithographs sufficient space to circulate freely around the poems, playing with them, and often spilling over into the margins.

When published, Parallèlement was both scathingly criticized and highly acclaimed. One writer condemned it as "uncertain stutterings," while another claimed that never before had illustrations been so perfectly adapted to verse. The work met with little immediate success and, over the years, most of the 200 copies remained unsold. In retrospect, however, Parallèlement marks a turning point in the history of the illustrated book.

Was Vollard intentionally provocative, seeking to create a scandal for his own advancement, or simply inspired? He in any case was undiscouraged, undertaking the following year a second project with Bonnard.

Let's take a closer look...

* "Il n'est pas étonnant qu'Ambroise Vollard ait songé à Bonnard pour illustrer Parallèlement de Verlaine. Il connaissait les dessins de l'artiste pour Marie; et il avait vu le tableau L'indolente, dont un dessin figurera d'ailleurs dans l'ouvrage, à l'exposition de groupe organisée chez Durand-Ruel en mai 1899. Pour accompagner les poèmes de Verlaine, Bonnard invente une composition irrégulière; les lithographies jouent avec les strophes, les enlacent, se mêlent à elles ou se glissent dans les marges, images voluptueuses et tendres dont le pouvoir de suggestion s'allie miraculeusement à l'art du poète." In Antoine Terrrasse, Pierre Bonnard, 1967, p. 61

** For a general discussion of Bonnard's use of photography in his art, see F. Heilbrun & P. Néagu, 1987, Bonnard Photographe, Dossiers du Musée d'Orsay 16.

*** "'Parallèlement' à Sagesse, Amour, et aussi à Bonheur qui va suivre et conclure. Après viendront, si Dieu le permet, des oeuvres impersonnelles avec l'intimité latérale d'un long Et cætera plus que probable. Ceci devrait être dit pour répondre aux objections que pourrait soulever le ton particulier du présent fragment d'un ensemble en train."

Lithographs in rose-sanguine over printed typography, 1900, on heavy wove paper, with the watermark PARALLELEMENT; the complete album of 136 pages, vertically folded and assembled in 17 cahiers, format 350 x 250 mm, never bound, and thus lacking the title page, table of contents, and justification, probably a printer's or artist's proof copy, aside from the first edition, with several of the rare colour variants in bistre*, very fine and fresh impressions with full margins, with deckle edges all around, some slight discolouration on the first and last pages from an old wrapper, sheet edges on certain pages slightly soiled and scuffed, otherwise in excellent condition.

Bibliography: Roger-Marx 94, Bouvet 73

* These bistre variants are quite well known, but poorly documented. Claude Roger-Marx, followed by Bouvet, simply states:

"Lithographs printed in rose-sanguine; certain of them, rare, with an additional plate of bistre."

["Lithographies tirées en rose-sanguine; certaines, rares, avec une planche supplementaire de bistre."]First of all, it is curious that they make mention of a plate, in that lithographs were then printed almost exclusively from stones, thick slabs of very fine-grained limestone (see GLOSSARY), not plates, especially in a prestigious workshop such as Auguste Clot's.

Secondly, examining the prints, it does not appear that a second stone was used. By 1900, Bonnard was already a master of colour lithography, and his artful and resourceful use of colour fields and textures over the previous decade (from his first poster France Champagne, which influenced Toulouse-Lautrec, to the album Quelques Aspects de la Vie de Paris) is well known. The bistre on these lithographs seems to have been added by hand, more as if they were experiments in colouring, or shading, on the keystone itself. We have also been able to compare the present copy with the "exemplaire d'auteur/editeur" (as annotated and signed by Vollard himself), now in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which contains 6 or 7 of these bistre variants (some of which are quite faint), and there are differences: although the overall handling of the bistre on the page 17 lithograph for Eté is practically identical, the lithographs on pages 42-43 for A Madame *** are not, the small dog on the right in the present copy having been more extensively touched with bistre.

N.B. For practical reasons, and given the size of the cahiers, we have decided to show them here in series, subdivided by section, on a small 1 : 4 scale as follows:

Part I: Dédicace & Les Amies, pages 1-20;

Part II: Filles, pages 21-44,

and with each of the larger images (1 : 2 scale) visible on a separate page.

Verlaine opens his "parallel" poetic argument with an invective dedication to his wife, Mathilde, chastising her as a "little goose" (with the erotic connotation of preliminary sexual advances, "les préludes d'amour", cf. La Fontaine), playing on his formative role, his ardent passion, her subsequent reticences and her "widowed heart", thereby addressing in a broader sense the bourgeois complacency of the Second Empire.

Further, in Allégorie, presumptuous Classicism is taken to task, with its worn clichés, which Verlaine purposefully intends to ignore, declaring that here he is creating a personal work.

|

Dédicace [Dedication], page 1Following Verlaine, Bonnard shows us the staid representation of a mid-century lady, hair in curls, primly seated, dressed in taffeta and bows, a small volume in hand, open across her knee, pensive, as if... |

|

Dédicace (continued), pages 2-3Here, Bonnard simply illustrates the writer's craft (and vocation!) embodied by the tools of the trade: a few scattered sheets of paper, an inkwell... |

|

Allégorie [Allegory], pages 4-5This "saddening" bucolic scenography of a lofty ancient temple features the amorous encounter of an aging naiad and faun, in the copse on the left, ... |

|

Allégorie (continued), Les Amies (title), pages 6-7and concluding on the classical theme of satyr and nymph as "outmoded staging," both Verlaine and Bonnard invite us to turn the page... |

The first section of Parallèlement comprises six sonnets on the theme of lesbianism, source of its scandalous reputation. A work from Verlaine's youth, it was originally published in Belgium, in 1867, under a pseudonym, where it was promptly banned.

The first five sonnets, written entirely in feminine rhymes, evoke the innocent amorous relations of adolescent girls, in a cycle that runs from autumn to summer, set in warm, fragrant, dark interiors, under an ever-present moon.

Sappho, the final sonnet, relates the legendary suicide of the ancient Greek poetess, due to her unrequited love for Phaon. She sings of her love to sleeping virgins before jumping from a cliff into the sea.

|

Sur le Balcon [On the Balcony], pages 8-9The balcony appears amidst luxuriant vegetation and circling swallows. Only the medallion to the left, the brunette and the blonde in intimate embrace, prefigures the text. |

|

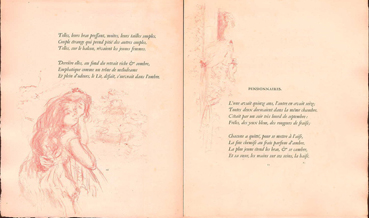

Sur le Balcon (continued), Pensionnaires [Boarders], pages 10-11A "strange couple" embraces before an unmade bed. Set in a boarding school in September, Pensionnaires insists on their youth (15 and 16 years old) and the spontaneous audacity of their erotic gestures that appear clearly on the following page. |

|

Pensionnaires (continued), Per Amica Silentia, pages 12-13The title of the poem, "By Amicable Silences," probably comes from a passage in the Aeniad, referring to the silent complicity of the moon in the girls' "friendship," set in a lamp-lit interior of undulating muslin curtains. |

|

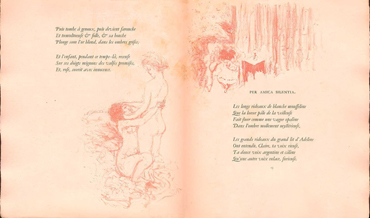

Per Amica Silentia (continued), Printemps [Spring], pages 14-15The girls embrace with abandon ("Aimons, aimons!"), and their mounting springtime love is compared to the sap rising in a flower, alluded to in a floral bouquet on the right. |

|

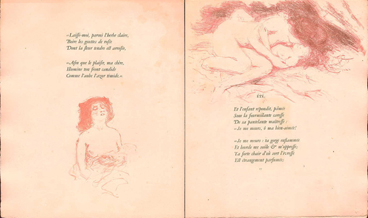

Printemps (continued), Eté [Summer], pages 16-17The closing image of Printemps shows the girl in a swoon under the ecstatic caress of her friend. Eté evokes the "strange perfume" of the flesh in a passionate embrace, the "dark charm of their summery maturities" prolonged onto the next page, below. N.B. The lithograph on page 17, one of Bonnard's best known, is furthermore one of the rare bistre colour variants as described above. |

|

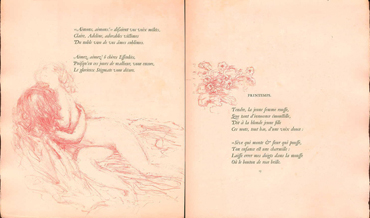

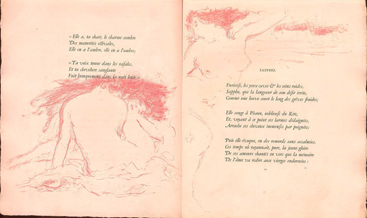

Eté (continued), Sappho, pages 18-19This inverted sonnet refers to Sappho's "inverted" love for Phaon (a male sailor), her subsequent rage at seeing him escape her desire... |

|

Sappho (continued), Filles (title), pages 20-21.and concludes on Sappho's disappearance into the dark waters of a moonlit sea, an allusion to Verlaine's own deep despair.

|