|

Exhibition

|

|

Exhibition

|

Here we intend to show complete sets of fine prints, either small thematic collections, whole series, or albums of special interest, with some general remarks as to their creation and their importance.

This space will be renewed regularly, with the previous exhibitions accessible thereafter in the Archives.

The present exhibition concerns a fine unbound set of Delacroix's Hamlet, comprising the complete first edition (and first issue) of the 13 lithographic prints as published by Delacroix in 1843.

This set is of particular interest for several reasons:

First published at the author's expense, the initial printing was exceedingly small, with only a few sets on chine appliqué. The album was not at first publicly acclaimed (L'Artiste going so far as to evoke its "pages désolantes" that the artist would better have kept in his portfolios). Later on, other art critics, such as Paul de Saint-Victor (in La Presse, 31 May 1864) were however quite enthusiastic:

It was thus critically acknowledged, though late, and the album was

often reprinted to meet the demand, even after his death.

Most importantly it is now esteemed as one of the masterpieces of 19th-century illustration, and certainly Delacroix's most accomplished graphic undertaking, which took him more than ten years to achieve; it is generally considered to be one of the first modern livres de peintre.

Eugène

Delacroix (1798-1863), the renowned French Romantic painter and

printmaker, was a key

figure in the emergence of modern art, and Hamlet,his

second and last album of lithographs (and certainly his most

accomplished), was a splendid graphic undertaking, without parallel at

the time, that now stands as a milestone at the forefront of this

development.

Hamlet,his

second and last album of lithographs (and certainly his most

accomplished), was a splendid graphic undertaking, without parallel at

the time, that now stands as a milestone at the forefront of this

development.

Furthermore, his long-standing interest in lithography, then an innovative graphic technique that he regularly explored since 1819 (leading to the realization of his first album of literary illustrations for Faust that he published in 1828), is here significant.

Delacroix considered himself to be "d'un naturel assez cosmopolite" (rather cosmopolitan by nature)*, as was his artistic curiosity: he sought inspiration from a variety of sources, and his avid interest in literature and theatre is quite well documented. During the summer of 1825, he travelled to England, spending several months in London, and often went to the theatre. He was especially fond of Shakespeare ("Les expressions d'admiration manquent pour la génie de Shakespeare.") and at the end of his stay asserted that he was "inconsolable d'avoir manqué Hamlet par Young."*

In 1827, he was

however able to attend a performance of Hamlet by an English company at the Odéon theatre in Paris, with Charles Kemble (right)

as Hamlet. (Note the "Elizabethan" garb then in theatrical

fashion.)

Odéon theatre in Paris, with Charles Kemble (right)

as Hamlet. (Note the "Elizabethan" garb then in theatrical

fashion.)

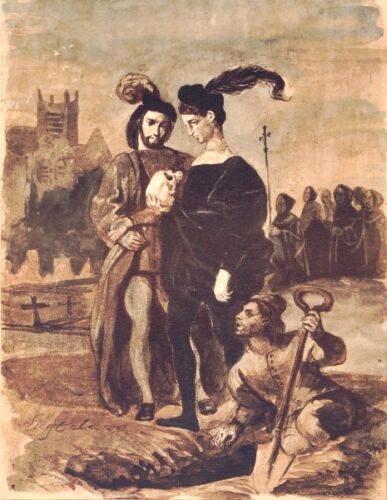

This so stimulated his fervent creativity that he produced a large lithograph (left) the following year of the famous graveyard scene (Act V, Scene I), wherein a rather gawky and grim Hamlet stands contemplating the skull of Yorick, before a dramatically expressive diagonal composition of hooded mourners under a dark veil of scudding clouds, with twilight spreading erratically at the horizon.

Replicating closely the central action of this scene

(in reverse),

there is a finely detailed ink-and-watercolour drawing

(left)

in a vertical format that Lee Johnson** links to an early painting

(L140, currently lost), and which he dates to the second half of the

1820s, his attribution probably based on stylistic similarites with the

lithograph.

Replicating closely the central action of this scene

(in reverse),

there is a finely detailed ink-and-watercolour drawing

(left)

in a vertical format that Lee Johnson** links to an early painting

(L140, currently lost), and which he dates to the second half of the

1820s, his attribution probably based on stylistic similarites with the

lithograph.

It is not clear

however if this drawing predates the lithograph.

Delacroix would again paint the same crucial scene, much darker now,

playing off a sickly green foreground

with tenebrous orange aloft, in a small horizontal format, in 1859 (right,

Musée du Louvre), just a few years before

his death, endowed with a more mature (and

bearded) Hamlet, with the same sombre torch-lit procession approaching

the tomb, bearing the coffin

of Ophelia in the lead.

tenebrous orange aloft, in a small horizontal format, in 1859 (right,

Musée du Louvre), just a few years before

his death, endowed with a more mature (and

bearded) Hamlet, with the same sombre torch-lit procession approaching

the tomb, bearing the coffin

of Ophelia in the lead.

But we're getting ahead of ourselves, and the main consideration of this on-line exhibition: the manner in which Delacroix developped this album as a coherent and innovative graphic project.

Hamlet was first published in 1843 by the Gihaut brothers in Paris, and printed by Villain.

Let's take a closer look...

* See Lettres de Eugène Delacroix (1815 à 1863) / recueillies et publiées par M. Philippe Burty, Paris, 1878, notably pages 70-80.

Yet there has long been a quibble in the air...

Publishing for the first time the extraordinary Hamlet sees the Ghost of his Father (see illustration and discussion below) as an "unknown picture" in the Jagiellonian University Museum, Krakow, Jadwiga Zebracka-Krupinska ("Nieznane obrazy Eugeniusza Delacroix w zbiorach Krakowskich", Folia HistoriaeArtium, III, Krakow [1966], pp.69-93) conducted a stylistic analysis of the work and concluded a date of 1845(?), which is curiously also the date given by Alfred Robaut (L’œuvre complet d’Eugène Delacroix, Paris, Charavay frères éditeurs, 1885).

Lee Johnson (The Paintings of Eugène Delacroix, Oxford University Press, 1981-1989) who first cited the work as lost (L99), subsequently maintains (in his following article, "Delacroix, Dumas and 'Hamlet'," The Burlington Magazine, Volume 123, December 1981) that indeed, it is signed and clearly dated 1825. He furthermore believes that Delacroix may well have seen the play in London in 1825 (only regretting the performance by Young, thus supposing that several versions of the play were staged that summer), and that this served as inspiration for the picture:

It has never been clear whether Delacroix attended a performance of Hamlet by the ill-received English troupe which played in Paris in 1822, nor do his writings make it certain that he saw the play in London in the summer of 1825; it is known only that he was disappointed to have missed seeing Young as Hamlet when in London. But given the date of his Hamlet sees the Ghost of his Father, it seems most likely to have been influenced by a performance seen in London.

** See Lee Johnson, The Paintings of Eugène Delacroix, Oxford University Press, 1981-1989, for a general discussion of these versions.

Beyond the scope of the present study, Johnson has catalogued a number of paintings of various subjects from Hamlet, notably:

- 2 versions of Hamlet sees the Ghost of his Father (one of which, cited above, is quite close to the lithograph D105. See also the discussion below...

- 6 versions of Hamlet and Horatio in the Graveyard (including the above),

- 3 versions of the Death of Ophelia (also including one from 1859),

- as well as Hamlet about to Kill Polonius (1848/9), Hamlet and the King at his Prayers (1848/9?), Hamlet abuses Ophelia (1849/50), and lastly Hamlet and the Body of Polonius (1855/6), all of which are very close to the lithographs in composition.

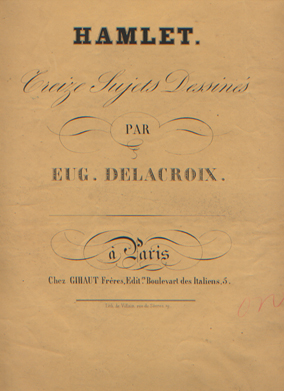

Lithographs, 1834-1843, printed in black on white chine appliqué to heavy wove paper, with no visible watermark, format 542 x 362 mm; the complete album of 13 plates, never bound, including the rare original title page on tan wove paper with the Gihaut Frères address, one of only twenty albums from the rare first issue of the first edition (the total print run for this first edition was twenty impressions on chine, plus sixty on a white wove paper*); very fine impressions with the lettering, with full margins, some foxing overall on the first and last pages (progressively reduced on the subsequent pages), sheet edges slightly soiled and scuffed, otherwise in excellent condition.

Bibliography:

Delteil, Loys. Le Peintre-graveur Illustré, Tome III: Ingres et Delacroix, Paris 1908.

Delteil, Loys (and Strauber, Susan). Delacroix, The Graphic Work: A Catalogue Raisonné, San Francisco, 1997.

Robaut, Alfred and Chesneau, Ernest. L'Oeuvre complet d'Eugène Delacroix. Peintures, Dessins, Gravures, Lithographies, Paris 1885.

Sérullaz, Maurice. Dessins de Eugène Delacroix, 2 volumes, Paris, 1984.

* According to Robaut the chine paper in the first edition extended beyond the borderline by one or two centimetres on some of the impressions (which is here the case), and that although with letters, these impressions were highly sought after.

Furthermore, the second issue (or printing) of the Villain edition according to Strauber is characterized by a number of alterations to the lithographic stones that make them rather easily identifiable; we shall mention them individually below.

Delacroix carefully worked on his thirteen lithographs (he would however add three lithographs to the 1864 edition) over a ten-year period*, although he mentions working on a lithography for the Gihaut brothers as early as 1824 in his Journal (Plon-Nourrit, Paris, 1893-1895,Tome I, page 97: "Samedi 24 [avril] - Le matin, travaillé à la lithographie pour Gihaut").

Graphically elaborated**, the work was conceived in a larger format than the Faust, and Delacroix published the album with no other text than the Shakespearian captions (in French), printed below each image.

We have included the original English text from the MIT online edition (http://shakespeare.mit.edu), which appears to follow the 1982 Arden edition, published by Methuen, edited by Harold Jenkins.

Here we give the dimensions of each image (height by width), as measured between the borderlines; the references to the lithographs are taken from the Delteil catalogue.

|

Eugène Delacroix's Hamlet / Treize Sujets Dessinéspublished by Gihaut Frères, Paris, 1843(rare first edition, cover)Delteil 102bis |

|

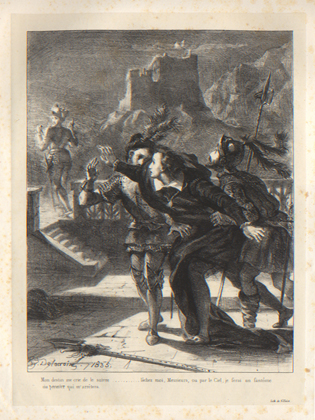

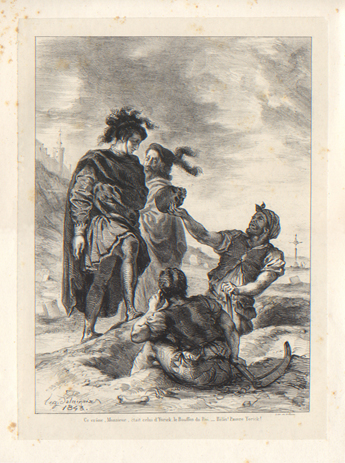

Hamlet tries to follow his Father's Ghost (D. 104)Mon destin me crie de le suivre ... lâchez-moi, Messieurs, ou par le Ciel, je ferai un fantôme / du premier qui m'arrêtera.[Hamlet:

Still am I called. Unhand me, Gentlemen. / By heaven, I'll make a

ghost of him that lets me!]

|

|

The Ghost on the Terrace (D. 105)Je suis l'esprit de ton père! ...Venge le d'un meurtre infâme et dénaturé.[Ghost: I

am thy father's spirit, ... /Till the foul crimes done in my days of

nature / Are burnt and

purged away.]

|

|

Polonius and Hamlet (D. 106)Que lisez-vous, Monseigneur? Des mots, des mots, des mots.[Polonius: What do you read, my lord?

Hamlet: Words, words, words.]

|

N.B. Following D106, in the second edition (1864), Delacroix added another lithograph to introduce Ophelia (D107), depicting the prince's encounter with her (following his famous "To be or not to be..." soliloquy), wherein he evokes her honesty and admonishes her with "Get thee to a nunnery..." (Act III, Scene I).

|

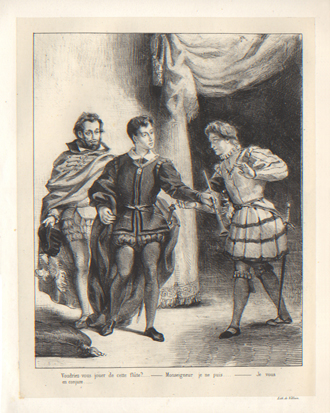

Hamlet and Guildenstern (D. 108)Voudriez-vous jouer de cette flûte? ... — Monseigneur je ne puis. ... — Je vous en conjure...[Hamlet:

Will you play upon this pipe? Guildenstern:

My lord, I

cannot. Hamlet: I pray you.]

|

Hamlet has the Actors play the

Scene

|

C'est une intrigue scélérate, mais qu'importe? Votre Majesté et nous avons la conscience libre, cela ne nous touche en rien ... vous voyez : il l'empoisonne dans le jardin pour s'emparer de son / royaume ... l'histoire est réelle, écrite en bel italien.["...

'tis a knavish piece of work: but what o' / that? your majesty and we

that have free souls, it / touches us not ... He poisons him i' the

garden for's estate... the story is extant, and writ in / choice

Italian..."]

|

|

Hamlet attempts to kill the King (D. 110)A présent je puis le tuer facilement ... mais quoi! le surprendrais-je au milieu de ses prières, au moment où il purifie son âme! non, non, — Ô conscience plus noire que la mort! âme engluée dans le crime! je ne puis prier! ... mes paroles s'adressent là-haut, mes pensées demeurent, ici bas.[Hamlet: Now might I do it pat, now he is praying; / ... and am I then revenged, / To take him in the purging of his soul, / ... No! ... / And that his soul may be as damn'd and black / As hell, whereto it goes...King Claudius: My words fly up, my thoughts remain below...]- Act III, Scene IIIHamlet is now sure of the king's fratricidal guilt and the revenge he must inevitably take. He is however unsure of his means of action. Here he happens upon the king, who in remorse for his misdeed kneels, repenting, in prayer. Delacroix depicts Hamlet about to draw his sword, determined to conclude his oath, although hesitating at such a pious moment. Signed and dated 1843. |

|

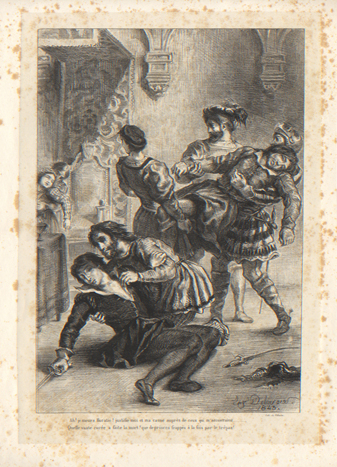

The Murder of Polonius (D. 111)Qu'est-ce donc? ... Un rat[Hamlet: How now? A rat!]

|

|

Hamlet and the Queen (D. 112)N'ajoute rien de plus: ces mots penètrent jusqu'à mon oreille comme autant de poignards / rien de plus, cher Hamlet![Queen Gertrude: O speak to me no

more; / These words, like daggers, enter in mine ears; / No more, sweet

Hamlet!]

|

|

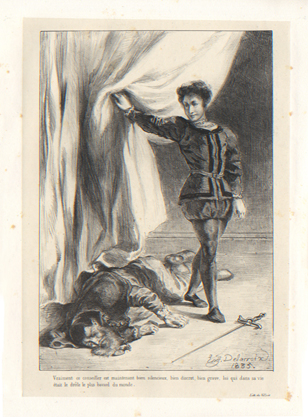

Hamlet and the Corpse of Polonius (D. 113)Vraiment ce conseiller est maintenant bien silencieux, bien discret, bien grave, lui qui a était le drôle le plus bavard du monde. [Hamlet:

Indeed this counsellor / Is

now most still, most secret and most grave, / Who was in life a foolish

prating knave.]

|

N.B. Following Hamlet and the Corpse of Polonius, in the second edition (1864), Delacroix added another lithograph, Ophelia's Song (D. 114), depicting her mad lamento (Act IV, Scene V) resulting from her love for Hamlet betrayed. It is worthwhile noting that, although the lithograph is dated 1834 (and thus one of the earliest), he initially chose not to include it in his own first edition. The personnage was thus twice excluded from the first edition, and thus appears here only in the scene of the enactment, and in the following illustration, which is, remarkably, one of the best known...

The Death of Ophelia (D. 115) |

... Ses vêtements appesantis et trempés d'eau ont entrainé la pauvre malheureuse.[Queen Gertrude: Till that her garments, heavy with their drink, / Pull'd the poor wretch...]

|

|

Hamlet and Horatio with the Gravediggers (D. 116)Ce crâne, Monsieur, était celui d'Yorick, le Bouffon du Roi. — Hélas! Pauvre Yorick |

Hamlet's Death (D. 118)Ah! je meurs Horatie! justifie moi et ma cause auprès de ceux qui m'accuseraient ... / Quelle vaste curée a faite la mort! que de princes frappés à la fois par le trépas![Hamlet: Horatio, I am dead; / ... report me and my cause aright / To the unsatisfied...Prince Fortinbras (the English ambassador): This quarry cries on havoc. O proud

death, ... / That thou so many princes at a shot / So bloodily hast

struck?]

|

Delacroix carefully thought out the Hamlet album, for more than ten years adding, deleting, and refining his vision of the play that had so strongly marked him years earlier*. His main efforts however are focused on 2 periods, 1834-1835 and 1843.

Twelve (of the sixteen) lithographs are dated, all covering three years: 1834 , 1835, and 1843.

Chronologically, he started the series in 1834 with D 103, D112, and D 114: Hamlet and the Queen are thus the focus and the starting point, while the third early print, Ophelia's Song, was curiously left out of his first edition, for reasons unknown.

The three lithographs dated 1835 (D 104, D 109, and D 113) define three "crucial" scenes: Hamlet's pursuit of his father's ghost, the enactment of the poisoning, and the death of Polonius.

The six lithographs dated 1843 complete three main sequences of the play:

- D 105 (following the pursuit), Hamlet's confrontation of his father's ghost (wherein his call to vengeance is made clear);

- D 110 (subsequent to the enactment scene), Hamlet's vain attempt to kill the King while at prayer;

- and D 115, 116, 117, and 118, the last four lithographs (covering the high point of the dramatic crescendo, drawing inevitably to the fatal conclusion), from Ophelia's drowning to the final death scene. For the first edition, Delacroix only chose to eliminate D 117, the scene of the struggle between Hamlet and Laertes in the open grave...

Of the four undated lithographs (D 6, 7, 8, and 11) the first three can be grouped together, composing a sequence of expository scenes for Polonius, Ophelia, and Guildenstern, setting the stage so to speak. (Only D7, Hamlet's rebuking of Ophelia, was excluded from the first edition.)

The fourth (D11), with Polonius (hidden behind the curtain) and Hamlet (sword drawn), explains the case of mistaken identity, and follows up on the previous lithograph of Hamlet's intentions to kill Claudius. (We have already noted the disparity in dress between D11 and D12, although D11 is consistent with D13.)

In preparing Hamlet, Delacroix made a number of drawings, showing an attentive elaboration of detail in refining pose, placement of figures, and garb for each scene of the album. He had a clear vision of what he sought well before the final lithographic version, with the scenes practically laid out in full, with few pentimenti.

Maurice Sérullaz (1984) published four of these sketches (now in the Louvre, and traceable to a single lot in Delacroix's estate sale). None of them unfortunately is dated, and there is no indication that they are contemporaneous. These correspond closely to the lithographs D103, D105, D108, and D115.

We have chosen to show two of them here as exemplary of Delacroix's working technique:

Groupe de Personages dont un Roi et une Reine (left, RF 32252) is the detailed study for The Queen tries to console Hamlet (D103), the first lithograph of the album. Delacroix here frames the central composition with King and Queen in a broad format, on either side of the hesitant Hamlet, here barely outlined so as to mark the full layout, and Delacroix elaborates the gestural refinements of the central figure of Hamlet on either side. The only major pentimento is the King's gesture, here arm outstreched, whereas in the lithogaraph he recoils in a sudden revulsive gesture. And the recalcitrant Hamlet comes to the fore, in a sketchy setting that leads to the finalized background, incorporating various architectural elements from the original sketch.

The more refined sketch (on the left) is remarkably close the the final (inverted) scenogaphy of the lithograph, and demonstrates Delacroix's clear conception of each scene in the series. The figure of Hamlet is practically identical, including the seething drapery and the pointing index finger, whereas Delacroix has reversed the king's gesture, looking right as he raises his hand to the visor of his helmet, whether raising it, and shielding his eyes from the dawn (thus assuring his identity), and holds the regal baton in his right hand, as was customary.

There is furthermore a pictorial version of this same key subject (left, Jagiellonian University Museum, Krakow**) that is considered by Lee Johnson to be Delacroix's earliest Hamlet-inspired painting (dated 1825!) and it is remarkably close to the lithograph (which, as may be recalled, is dated 1843).

He however seems to consider the picture to be rather approximative:

It is

not so accomplished a picture as the others from the 1820s listed by

Dumas: the king is weakly modelled, even for a ghost, Hamlet's action

undirected, the setting a monotonous and obtrusive row of cardboard

cylinders poorly related to the figures...

Would this thus have been the première pensée of this key scene, reproduced lithographically 18 years later, with greater attention to setting and detail, for the album...

It is however remarkably close to the lithographic version, and the subject is not

inverted (contrary to the sketch above!), as is required by the drawing

on stone. The spectral king is somewhat set back from the

immediate

foreground, his sword varying in position (here, as is customary, hung

to the left), while Hamlet's stride is broader and his right-hand

gesture unsure, but the overall similarity of effect is striking.

The chiaroscuro highlights

of the pre-dawn scene are also quite close to the lithography, bathing centre

stage in a wan glow, with the two figures dramatically framed in their

confrontation; the scenography is simple yet forceful.

There are also three drawings in the Karen B. Cohen Collection (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), that were shown at the Musée Delacroix in Paris from December 2009 to April 2010:

- Étude pour Hamlet et la Reine,

- Étude pour Hamlet et Laertes dans la Fosse d’Ophélie,

- Étude pour La Mort de Hamlet.

Lastly, there is a fine sketch of a reflective Hamlet, book in hand (now in the Musée Bonnat, Bayonne), for D106, and there have been several drawings on the art market in recent years (e.g. Koller, Zurich, 18 March 2008, Lot 3560 Kniender König im Gebet mit Hamlet den Raum betretend, i.e., the King kneeling at Prayer) that complete this series.

In conclusion, through his lithographic dramaturgy for Hamlet,

Delacroix

provides powerful and succinct visual equivalences of the key scenes in

the play. He does not stage them as theatrical performances per se;

his refined settings are rather ambient visions setting the scene

(sometimes spare, sometimes spectacular, or even occasionally

naturalistic, i.e. the drowned Ophelia), condensed renderings of his

"romantic" imagination that enfold the action. His figures are

nevertheless studied, highly dramatic, and larger than life, each

gesture, each countenace, each pose complementing the meaningful action

of the scene, and sounding out the depths of Hamlet's being.

Robert Edenbaum (1967), in analyzing the Hamlet suite, concluded:

"Delacroix was

very much concerned with the particular in situation and emotion; he

was not interested in being consistent from one lithograph to the next

but in exploiting each scene for its own sake and each facet of

Hamlet's character as profoundly as possible." ***

As we may also see in the drawings, where his vision was laid out clearly from the beginning, this lithographic suite is among his most mature and accomplished works.

Following the commentary on the Musée Delacroix website (recalling the initial critical response to the album that was either quite reserved or simply negative):

"Today, they are now considered to be among the artist’s most important creations, one of the works into which he poured his soul."

* Delacroix however seems to have interrupted this project in 1836, more taken up with public commissions (Palais Bourbon, Palais du Luxembourg), and resuming his work on Hamlet in 1842, as may be surmised by the dating of the prints.

** See Lee Johnson's article, 1981 (above), for an extended discussion of the picture, and its probable provenance from Alexandre Dumas.

*** Robert Edenbaum, "Delacroix's 'Hamlet' Studies", in Art Journal, Vol. 26, No. 4, 1967, page 351.