|

Exhibition

|

|

Exhibition

|

The picture (right)

is painted on a small

oak panel, 196 x 134 mm., from the collection of James Orrock

Esq., which was sold at Christie's first in 1895, and later in 1926, according to

the inventory number, 297 E.F., that is stenciled on the verso.

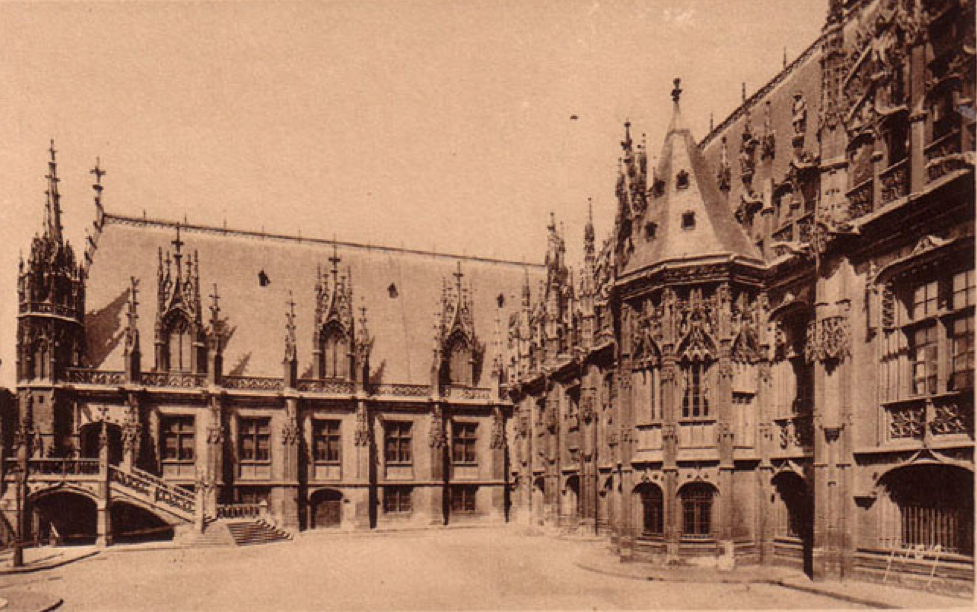

L'Entrée de la Salle des Pas Perdus is depicted from the east, in a clear mid-morning light, showing a variety of figures at the foot of stairway, who are going about their various businesses.

The picture corresponds roughly to the left two-thirds of the lithograph (below, left), framing the entranceway to the hall, under an awning that partially shades the staircase.

The truncated spire, decorated with ornate niches, crockets, and pinnacles, rises above an octagonal tower, dominating the entire scene, set against a luminous sky and the steep verdigris roof of the hallway. It frames the dark entranceway with another high-gabled Gothic window.

Human activity makes up the main part of the lower composition, and is practically unchanged in the lithograph. The figures however all seem rather anachronistic, as the artist seeks to recreate a lively scene that would have taken place in the 17th century.

In the foreground (left to right),

there are two tonsured monks

(probably Franciscans), a magistrate

(identifiable by his toque, red robe and pendant cravat), in discussion with two

elegant gentlemen, both

wearing broad-brimmed hats with colourful panaches, short  capes,

culottes, and wide-topped

cavalier boots. Behind them, a figure dressed all in black

(possibly a Jew, as the Palais was originally built in the Clos aux Juifs), a pikeman on the staircase, and another magistrate

approaching from the right. Various other people are moving

around the entranceway, and there seems to be another magistrate at the

top of the stairs.

capes,

culottes, and wide-topped

cavalier boots. Behind them, a figure dressed all in black

(possibly a Jew, as the Palais was originally built in the Clos aux Juifs), a pikeman on the staircase, and another magistrate

approaching from the right. Various other people are moving

around the entranceway, and there seems to be another magistrate at the

top of the stairs.

There are however rather significant variants between the picture and the lithograph.

The modified perspective is the most notable, with the viewpoint much closer in the picture, and a bit farther to the right, emphasising the monumental spire and the angle of the receding row of buildings to the far left. Consequently, the stairway has been purposely shortened, which gives the edifice a grander scale and allows the artist to focus on the lively scene at its foot.

The time of day too is a bit different,, the light in the picture somewhat earlier, judging by the cast shadow of the spire.

More puzzling, though, high above the damaged cornice of the entranceway, is the dormer window, which is visible in the lithograph, but clearly absent in the picture.

We know that Bonington gave more attention to effect than fussy detail; what indeed did the building look like in Bonington's time?

Bonington's representation of the architecture seems relatively faithful, though the exact state of the edifice in the early 1820s is in part conjectural, and requires some study.

It

is well known that the French Revolution took a rather exacting toll on

many public structures, but it appears that the Palais de Justice was already rather damaged before then.

There is an earlier allegorical engraving from 1774 (right), viewed from a similar perspective, which represents Jesus driving the Merchants from the Temple*, and which uses the entranceway of the Palais de Justice to stage it.

If we compare it to the two Bonington images, there are several

features that stand out:

- the spire is

already markedly broken (though this engraving shows a more pronounced torsade);

- the dormer window is not apparent, which corresponds to the picture, rather than to the lithograph;

- the large awning over the stairway is not yet in evidence;

- and the roof has an elaborate crest with finials that is lacking in both of Bonington's works.

The numerous storefronts, to the

right

of the stairway, are bookshops. (Rouen had been a major publishing

center since the Middle Ages.) These were condemned in 1792 and

subsequently torn down (see the article by Jean-Dominique Mellot,

below). One such shop still remains in Bonington's lithograph, to

the far right.

According to Pierre Chirol, the crest of the roof, which was made of lead, was torn down as well during the Revolution in order to make munitions.

* The allegory refers in fact to the expulsion of the Conseil Supérieur, which had been instituted by Louis XV in 1772 to replace the Parlement de Normandie.

* See for example the excerpt from a letter by Charles Silvester (who had patented a method of galvanization) that was published in the Journal des Mines, 1811 (http://annales.ensmp.fr/articles/1811-1/121-123.pdf), in which he states his preference for zinc as superior to copper in this capacity.

Bibliography:

E. Caude, Le Parlement de Normandie, Paris, 1999

Pierre Chirol, Palais de Justice de Rouen (Paris, 1928) see:

http://bibnum.enc.sorbonne.fr/gsdl/collect/tap/archives/HASHbed8/6423b1d2.dir/0000005294695.pdfP. A. Floquet, Histoire du Parlement de Normandie, Rouen, 1840-1842

François Guillet, L'Invention de la Normandie, a series of conferences given at the Université Populaire de Caen, 2010-2011; see http://upc.michelonfray.fr/intervenants/collectif-seminaire-normandie/archives-normandie/

Jean-Dominique Mellot, "La librarie du Palais sous l'Ancien regime: splendeur et décadence de l'exception rouennaise du livre" in Les parlements et la Vie de la Cité (XVIe - XVIIIe Siècle), under the Direction of O. Chaline et Y. Sassier, Université de Rouen, 2004

For the drawing by François-Gabriel-Théodore Basset de Jolimont, see: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b7740739z)